What if Superman opted to grow up into a bad guy instead of becoming a superhero?

The premise is bluntly to-the-point and apparent to anyone who has watched any of the trailers and- at least to me- as close to a surefire concept as it gets. Sure, it was far from an original idea, having been previously played in comic book form in some alternate version or another (Mark Millar’s Red Son) or verbatim (Mark Waid’s Irredeemable). The prospect of watching what, if not promised, at least strongly hinted at being thoroughly enjoyable and slightly trashy (in the most delicious fashion, too) take on the material was very enticing.

Alas. BRIGHTBURN, the concoction from director David Yarovesky and Journey 2: The Mysterious Island screenwriters Brian and Mark Gunn (James Gunn’s brother and cousin, respectively- hence the ubiquitous From the Visionary Creator of Guardians of the Galaxy title cards all over the marketing materials) is neither enjoyable nor even trashy. It ultimately settles for a disappointing mediocrity defined throughout by an infuriating indecisiveness.

The promised story is there, all right, but all of the myriad possible scenarios that might have played out fail actually to unfold- incredibly, the end of the movie leaves you feeling as if no scenario whatsoever played out at all. BRIGHTBURN is not an actual movie, but an elevator pitch come to quite inert life. There are ideas, plenty of them- which make the entire endeavor even more frustrating, but rather than choosing the best- or at the very least what they felt was the best- path to follow the filmmakers seem to have religiously implemented a strict policy of throwing everything at the wall in the hopes of something- anything- managing to stick.

The adherence to Superman lore is so complete one might consider Warner Brothers indeed thought this was a parody, thus not worth getting into any legal fuss over. A couple (Elizabeth Banks and David Denman) desperate (and unable) to conceive a child live in a farm in the small town of Brightburn, Kansas. One night, some kind of aircraft (of unknown origin since it doesn´t seem to be man- or earthling-made) crashes down in the woods nearby, and they find a baby inside whom, promptly, they proceed to take in as their own. Years pass by, and the baby (already christened with his properly alliterative name- Brandon Breyer- to keep the comic book motif going) is now a young kid (Jackson A. Dunn, recently seen by half mankind in Avengers: Endgame as Scott Lang’ 12-year-old self in the time-machine testing gag). But he is no ordinary kid: he can throw a lawnmower two hundred feet away and stick his fingers into its sharp, rotating blades only causing harm to the machine. He never gets sick. And only the metal of his own spaceship has ever made him bleed.

From there, the possibilities blossom. Ma and Pa Breyer find some magazine pages with photos of lingerie models under his mattress but, alongside, there are some absurdly detailed schematics of female genitalia, bringing up the question of whether there is some fundamental- maybe even Cronenbergian- the neurobiological difference between Brandon and the rest of humankind. The point is never brought up again.

We witness as he discovers his, apparently, very first display of super strength and invulnerability and, for a split second, we relish the chance to watch as he tests and looks for the exact reach of his limits and capabilities. However. a couple of scenes later- having shown us nothing in the interim- he is flat out flying and using full-on laser-ray vision as if he had been doing it since birth.

We meet him as a very intelligent (genius-level almost), quiet kid, target of every bully in sight, but there is not one single scene after he embraces his powers wherein he does something to exact any sort of revenge which comes off as stunningly baffling particularly since this is a story of power corrupting absolutely. Also, there are hints of him about to become a superpowered stalker when he enters his school crush’s bedroom in the middle of the night that are equally dropped and never come anywhere near to fruition.

His behavior is also depicted in the most ambivalent, incoherent way, one that has him acting like a normal kid one second (or pretending, for some unexplained reason) and the next causing mayhem and devastation with unhinged abandon. There is absolutely no arc (worse yet, not even the intention of crafting such) charting the turning of his back on the most basic human empathy and it goes from A to Z in one single step devoid of any layers whatsoever. “You are one of the few people who know who I really am, but one day the entire world will know,” he says to the girl he likes, and the only reaction such statement elicits is asking yourself: why not right now?

Dunn’s performance, arguably the one the entire film is dependent on, is lackluster, to put it mildly. The emotional range his face conveys is firmly entrenched in Hollywood’s usual depiction of people on the spectrum but I can’t, in good conscience, blame him, certainly not alone. Acting is the spawn of writing, and when this latter hardly knows what it wants to communicate in the first place, there is no satisfactory outcome in the horizon for anyone involved. This becomes painfully apparent when neither extremely likable Banks nor fan favorite Matt Jones (Breaking Bad’s Badger) manages to turn any of their screentime into anything memorable.

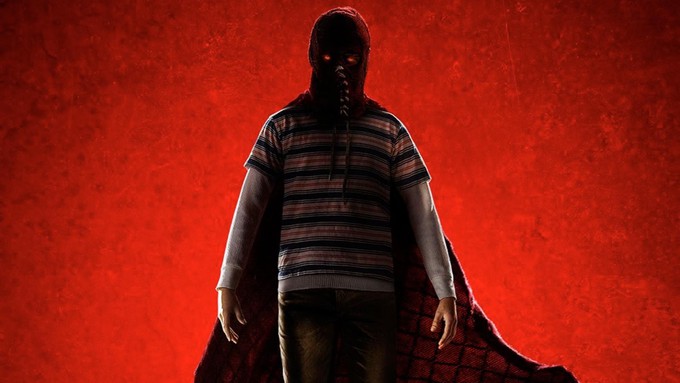

It is not as if there weren’t any inspired choices at all, either. The design of a kid’s twisted notion of what a “superhero” cum slasher should look like is very eye-catching and full with potential, denoting youth (Converse sneakers, jeans, striped polo shirt) and anonymous menace (worn out cloth mask with an ominous, quasi-Lovecraftian elephant trunk tied together with sneakers’ shoelaces) at once. The main logo, standing for both his and his town’s initials, was clever enough as well but I can´t think of more things worth lauding. Also by the time the end credits roll up, and Michael Rooker makes his obligatory appearance in a James Gunn production with a cameo as a conspiracy theorist denouncing the veiled existence of superpowered beings among us (thus setting up an evil Justice League to be developed in upcoming sequels), I had long since given up trying to find more. There are next to no thrills to be found here either looking at it from the perspective of a horror movie or from that of an action one, no suspense, no satisfactory build up to any momentum whatsoever.

There is no disappointment without expectations, and that is the main reason BRIGHTBURN is such a disheartening experience: this was an obvious story, so much so that one might even say it should have written itself, but in the end, it feels as if it was not written at all.

Eloy Ricardo Balderas Salazar