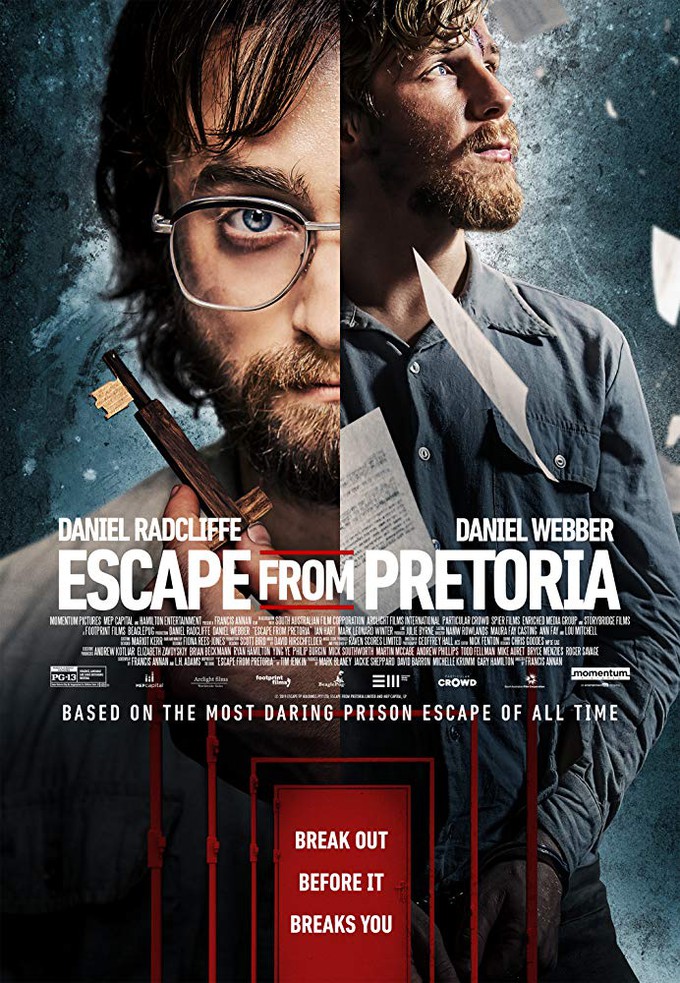

ekm Discusses ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA with Daniel Radcliffe, Francis Annan, and Daniel Webber

It’s March, which means it’s time for the home video and On Demand release of that film about an evil dictatorship, and the plucky resistance fighters who challenged tyranny. Since we can all agree that THE RISE OF SKYWALKER was garbage, however, I would direct you toward ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA, based on the true story of political prisoners Time Jenkin (Daniel Radcliffe) and Stephen Lee (Daniel Webber) instigating a prison break during the South African Apartheid. I was fortunate to see a screener of this film (which is the best of 2020 thus far, by my estimation), and had the pleasure of speaking with stars Radcliffe and Webber, as well as Writer/Director Francis Annan.*

ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA is now playing in select theaters, and available now for rental, purchase, and streaming.

DANIEL RADCLIFFE (as Tim Jenkin)

ekm: I want to talk a little about the film and your career in general. I find it endlessly fascinating that after coming up as a child actor in a major franchise, you’ve made the seemingly deliberate move into quirkier or offbeat work like EQUUS and SWISS ARMY MAN, and now, ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA. Can you tell me a little bit about that transition?

DR: You know, it’s mostly just inspired by the fact that I’m in a position to do things that I like. I mean, at first there was a feeling coming out of POTTER…there was definitely a certain amount of feeling that I had to prove that I could do lots of different things. That led to me always knowing that I wanted to have a wide variety in my work if that was possible. And I think a lot of my journey after POTTER has been me finding out what I’m good at and what I like. And it makes me really happy to do it, and I’m in the position to simply base my career around the things that make me happy to do, and I balance that with a pathological need to be working at all times, but I am getting better at not just doing things because I have the time, but picking the things that I love and that I know I’m going to love doing.

ekm: It seems like you were dipping the toe in the pool and challenging stereotypes as early as your appearance on EXTRAS (which I loved, by the way).

DR: (laughs) Yeah, well that was particularly about –- obviously, I’m a huge fan of Ricky Gervais and THE OFFICE, and just to be on the show was a big deal. And that was very fun to do acting-wise. But what it gave me the chance to do was to take the piss out of sort of ridiculous, arrogant, slightly braggadocious child star stereotypes. And, I can’t remember how old I was, probably fifteen or sixteen, so I was old enough to realize that’s what people probably thought I was, so he gave me a chance to take the piss out of it, and hopefully communicate to some people that it was not the person that I was.

ekm: Yeah, there have to be some mixed emotions about freeing yourself from the obligations of a machine like the HARRY POTTER franchise and the back-against-the-wall freedom of carving out a fresh identity with performances that allow you to challenge the public perception of who you are as an actor.

DR: Yeah, I mean –- that’s the thing: looking back during that crucible it wasn’t a big deal. It sort of showed people that I was willing to hedge up, and challenge myself, which I think was something people needed to see at that moment in time — you know, to believe that I was going to take being an actor seriously. And that was the case for a while. I’m sure to some people I’m still very much bridging that. But I’m feeling much more secure in who I am and my abilities, not that I still don’t have self-doubt or insecurity, but I definitely feel like –- if you had said to me ten years ago at the end of POTTER, if you had presented me with like the career that I have had since then, and said This is what you’re going to be doing for the next ten years, I would have bitten your hand off with delight. I’m sort of very happy with how it’s gone so far. There’s still time for it to go wrong! But I’m very happy.

ekm: As an actor who is so well known for a specific on-screen identity, what is that transformation like for you to play a character like Tim Jenkin, where you grow a beard and vanish into the physicality of the role?

DR: What’s funny is: the beard, I literally grow whenever I’m not working, because I hate shaving with a passion. The beard was like, they wanted me to grow it out, and I was like, “Yeah, great, that can be done.” And actually I was really resistant to the idea of a wig; I was just kind of trying to grow my hair out, but my hair does not do what Tim’s does even if I grow it, so they put the wig on. I was like, “Oh, actually, that is really good.” There is a lovely thing that happens, and it doesn’t happen on every job at all: sometimes I just look like myself, but on this one (and on KILL YOUR DARLINGS where I did the eyes and the hair, and on IMPREIUM, where I actually shaved my head), there is something very helpful sometime about when you look in the mirror and see a different person. It’s something sort of quite liberating, and you feel more liberated to push yourself into a different physicality, because you look so different.

ekm: It’s very, very interesting seeing you, whether you’re transforming physically like that, or something like SWISS ARMY MAN where you’re just absolutely taking the piss out of how the public sees you. That’s a fantastic thing. That’s gotta be liberating. Now, circling back to HARRY POTTER just briefly, tell me about working with Ian Hart again. You had your first dramatic scenes as a relatively new child actor with him [IN HARRY POTTER AND THE PHILOSOPHER’S STONE], and now you’re playing against him in ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA as a seasoned performer. That has to be a unique experience.

DR: It’s really cool, and it’s an experience I’m having more and more, and it’s both lovely and sort of a reminder to me that I’m getting older. I can’t even begin to imagine what for them it must be like, for the people on the other side of that. But for me, Ian has not changed at all. I said to him, “Why, you look the same as you looked twenty years ago,” and he was so nice. It’s really nice to work with him again as an adult, and get to do proper acting with him again. I’m also having that experience in the play I’m doing at the moment in London where one of the actors in it, a guy called Carl Johnson, who I worked with maybe on my second or third day ever on a film set on a film for the BBC when I was maybe nine, or just ten; and yeah, it’s a really cool thing that I’m gonna get for a while: working with people who I worked with twenty years ago.

ekm: Speaking of working with people, how much did you draw on the experiences of the real Tim Jenkin, who has a cameo in the film as a prisoner? Did you get to talk to him much?

DR: Yeah, we were really lucky, actually. We got to Skype with Tim and Steve for a bit, and we were able to ask, and in spite of having told his story about a hundred thousand times, he got very patient with us, and was great at answering all of our questions about his book, and he was on set as a very valuable resource. We could ask him about stuff and about how things worked. It was kind of intimidating to have him around, because we’re making his life into a film, but it was definitely a great resource.

ekm: So, Daniel, what do you have next, what’s next in the pipeline?

DR: So I’m doing this play right now, and that will take me to the end of March. I’ve got this film and I’ve also got GUNS AKIMBO coming out in quite quick succession. They’ve done like an interactive movie with THE UNBREAKABLE KIMMY SCHMIDT, and I’m in that, and that’s coming out in like the middle, I think…actually I don’t know when that’s coming out, but at some point in all this. I think after that I’m gonna take a break, and read some scripts and figure out what next. But I’m not rushing out, I’m going, I’ve been going since the middle of last year, so I’m okay to have a little break for a while.

ekm: Well, after WOMAN IN BLACK, I am dreaming of a big budget remake of DRACULA, with you as Jonathan Harker, or frankly anybody else in that story.** I loved WOMAN IN BLACK. I loved seeing Hammer return, and that you were on the flagship title there.

DR: I love that film! It’s a brilliantly made film, and yeah, I would love doing that! I really love that idea, so if anyone’s reading, make it so.

FRANCIS ANNAN (Writer/Director)

ekm: So, first of all, the very obvious questions: how did you first become aware of this story, and what was the path that led you to bringing it to the screen?

FA: I was interested in political thrillers. I think politics is thrilling in general. And it has that kind of haves and have-nots, and that struggle against injustice is sort of like a theme throughout, and I’ve always enjoyed those. And so I met with the producers, the British producers, in 2012, and I expressed my interest in political thrillers, and they said, “Oh, you know, in that case, we’ve got a book, Inside Out: Escape from Pretoria Prison, by Tim Jenkin. So I read the book, and annotated it, and highlighted it, and said, “Oh, we should do this, and do that, and cut here, and blah blah blah,” and they lost the rights for a period of time, and then got it back. And yeah, fate just took its course from there.

ekm: Obviously, life does not necessarily adhere to a three-act structure, and the bane of any film based on a true story is just that. Speaking as someone who has seen the film but not read the book, how much did you have to do in the way of compression or elimination?

FA: Yeah, it’s a lot of compression — about three-quarters of the book. The last three quarters of the book dedicated to the escape; and the mechanics of the escape; and the conditions in the prison; and about the first quarter, maybe first third, with them beforehand and what led them to join the anti-apartheid movement and their arrests; and the sentencing. So about one-quarter to about three quarters ratio. So this is a prison-break book; it’s about the prison. So, okay, well after all of that happened, originally there was so much juicy stuff, so much spy novel type stuff before they get sentenced, before they get captured; and I tried to put as much of that in, but as time went on we had to sort of pick a side almost. Is it a spy thriller or is it a prison break movie? And we sort of battled on it, and the decision was made that it would be a prison break movie because that’s what the book is. And so it sort of became about trying to truncate, distill, condense, the facts. The real prison escape attempts had a lot of repetition. They go to this place or that place lots of times. They try the thing out lots of times. It takes over 18 months all together. So I have to sort of try and find the main elements, and then conflate them, sort of condense something that would happen five, six, seven times, into one or two occasions. So having the book was useful to sort of say, Okay, this happened lots of times. Okay, you know when they went down all these times, when they went to this certain place or did this certain thing, these are the five or six things that they learned. I’ll take those five or six things and put them into one scene, to make it look as if it happened at once –- or, I will just take two of the main things that they learned and put that into a scene. So a lot of that was going on, to heighten the tension, and also to condense it, to make it sort of fit. And so yes, the condensing of facts was a big, happened a lot in the film.

ekm: Now, along those lines, you obviously had the book, but was Tim Jenkin involved in consulting on any level? Obviously you have him doing a cameo in the film, and I spoke to Daniel Radcliffe yesterday who told me that Jenkin was very helpful to him in finding the character and the motivations. Was that true for you as well?

FA: Yeah, I’d met Tim in 2013, I think for about three hours, and in 2015 in London for about 2.5 hours. I went to Cape Town and went to his house and had dinner and he showed me around over the real locations [in 2017] that they were at forty years ago, and then for two weeks during shooting. So, I had a lot of working with Tim. He also made a 25, 30-page dossier about the technical specificities of the key [created by the protagonists to escape the prison], and how this worked and how that worked and what it did. So that was very useful for myself and for the art department, for the designers, to have an idea of things. You know, bits in the film that came directly from his anecdotes on set, you know we had a certain feel and (inaudible) and in this one scene where — I won’t give too much away — where Dan Radcliff’s character has to hide something kind of on his [person], and you would kind of expect to hide the object might be a very sort of contorted, painful way, and Tim said, “No, actually, everything just sort of went a much more smooth process,” and we said, “Oh, okay, well then we’ll make it more like that.” And at the end of the film as well, without spoiling it, there’s an amazing sort of epiphany, a moment of joy, and Tim and Steven’s recounting of that event was a real sense of joy and relief, and again the actors really latched onto that and incorporated it into the final scenes of the film.

ekm: Have [Tim Jenkin and Stephen Lee] seen the film since it’s been finished, hand given you any sort of feedback or thought?

FA: Yeah, so we had a private screening. Stephen and Stephen’s wife had a private screening, with myself and the UK producers. And we had one this Sunday just gone, in Soho in London: a packed audience of 350 people with a Q&A at the end, and both times they were really sort of fascinated and loved the film. Stephen mentioned he was glad the political motivations had not been chewed up or cut down, and Tim said although he went in kind of wondering about the changes that might be made in the film, he went in and found himself engaging with the film, on a level he didn’t expect to. The film awakened those events and that memory again, which he found really striking, he didn’t expect that. So yeah, I think every time they’ve watched it they’ve seen new bits in it, and they sort of enjoy it more, which I think is really great to see an audience. It’s great to see everybody gasping and laughing and whooping. It’s really great to see the film being experienced by others, their story.

ekm: That’s got to be the highest compliment that you as a storyteller could possibly receive: that it’s such a harrowing life event, and for the individuals who lived it to respond to the fidelity of your storytelling — that’s got to be worth more than critical praise.

FA: Yeah, I mean that was…I’m not someone who gets nervous. I’m not particularly highly strung; I just take everything in stride. But I remember having their screening and thinking, “What is this feeling, anxiety or nervousness, for the first time?” I actually found myself going “Ah, I wasn’t ready for this.” Because they’re watching. I was nervous. So to hear what they said was lovely, and having watched it for a second time in a room full of people who were really involved, you know, kind of more than normal films: that was lovely, that was good to hear that. In spite of a lot of the truncating and condensing and “filmification,” if you will, the book to the film, it still felt like –- that was their experience. And that was good.

ekm: In terms of bringing their story to life, a lot of that obviously goes into the casting, and you have this great ensemble of character actors. You have Radcliffe, and you have Daniel Webber, but you have Ian Hart, and Stephen Hunter. What was the most important thing to you in terms of casting the film? Were you going for people who looked the part visually, were you capturing the spirit of the individuals, or were you going for a happy medium?

FA: I mean, acting ability, really, first. You know, was a huge thing, when you find someone –- the look was not insignificant. It was somewhere in my radar. But with wigs and beards and this sort of thing you can sort of get there. So, it was in my purview, but it was not the principal thing. But acting, because in this film, there’s a lot of extended non-dialogue scenes, where it goes two, two-and-a-half, three, three-and-a-half pages of no dialogue, just action. Wall-to-wall, top-to-bottom, quite intense action. And so I really needed somebody who wasn’t going to overact, people who weren’t going to overact, but people who weren’t going to be sort of boring to look at, or unphysical. They needed to be people who could convey tension and anxiety and trepidation, you know, with a look, or the body. And that was important to me, people who were interesting to look at and people who could act in a way that was very mature and tanned, people who were cinematically aware. Yeah, people who just felt right. You know, I remember seeing Stephen Hunter in particular, and just thinking, Yeah, he works, and the casting directors with me on that as well, and we approached, and we went to him. Ian Hart, he had a kind of gravitas that the character needed. But obviously I went to Daniel Radcliffe first, and I knew he was very inventive; he picked a lot of very interesting and nonconventional roles. All in all, I think Pratoria has a sort of commercial edge to it; it still has the sort of interesting elements to it, and I thought he would enjoy being so –- you know, an actor who can throw himself into things. So yeah, we were in preproduction, and his agent looked at the script, and he loved it, and we met, and in that meeting he just said, “Yeah mate, I love it, it’s great”. So we had him, knowing that he’s going to throw himself into the role, and everything’s off, let’s go.

ekm: This is a story that it’s themes, dealing with oppression but also dealing with the struggle and triumph of the everyman, is something that can speak to audiences all over the world, particularly in this present day. Is there any specific message that you are hoping personally, that viewers are going to take away from the film?

FA: You know, these two guys they believed Apartheid was wrong, racial segregation isn’t good, and we are all made equal in God’s image; that sort of thing. And to move from that to something very actual, and very costly potentially, is something that not everyone does. And so you’re watching two people put their money where their mouth is, be punished for it, and then find a way beyond all of that, to keep going, to find a way even in prison, to keep that idea alive. I think that’s –- I don’t want to give away the end too much –- but that scene at the end where Dan holds up the keys, and after all those months and all that time, he looks at this key that he made that’s given them this sense of victory. And you get that sense of, “Wow, you know an idea can be converted to an action.” A very simple but very powerful sense. But yeah, I think if you watch these two guys put themselves out there, you should be thinking, it’s an amazing thing, and you should be thinking, “Wow, you know, I can have an idea, and I can execute that idea, and it can lead to some real, actual, tangible change. What is my equivalent? What is the equivalent thing that I can do?” That’s interesting, I think, and just the sense that you should never gave up. Those guys never gave up, or gave out. And the film is a testament to that, and viewers can think about how they can apply that in their own lives.

DANIEL WEBBER (as Stephen Lee)

ekm: Well, sir, I was literally just watching THE DIRT for probably the thirty-seventh time when [you called]. I cannot tell you enough how much I love that movie, and how you capture Vince Neil so perfectly.

DW: (laughs) Oh, cheers man, that means a lot, thank you very much. Are you a Crue fan?

ekm: I was a Crue fan back in my younger days. I went to go see them live when I think I was fourteen. What about you? I’m assuming you had to do a pretty hefty amount of research of old music videos and what-not.

DW: Oh, yeah man, I had Motley Crue coming out of my ears. Yeah. I had two months of research before we went into rehearsals, and it was just a lot. Lived, breathed, and shat bloody Motley Crue for three or four months.

ekm: It’s an incredibly edgy film, and I’m wondering, is there an even edgier cut of the film that we’ve never seen?

DW: Uh, yeah, I’d say so. I think so. I mean, there’s maybe one scene we cut out. But, I think there’s the most part of what was in the script.

ekm: Awesome. I’ve seen your work in a lot of different films and series, and I’m always struck by your ability to vanish into the roll, so can you talk about your process, whether your playing a former soldier with PTSD in [the Netflix series] THE PUNISHER, or Lee Harvey Oswald, or Vince Neil in THE DIRT? What does your research include, and how do you apply it?

DW: God, I don’t want to be a wanker about this, but it is hard I think to talk about, because it is a lot of things that go into creating it. It’s kind of what we were just saying: it’s just research, and ingesting as much about this person or this character as you possibly can in the timeframe that you have. So for this film, for ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA, I saw Stephen Lee through the prism of what he did, which was sort of essentially take a stand against, fight against, his government. There was that strength to him, and that sort of humanity. And I was trying to understand him, and why he cared about this; like, what made him care, when he was in a country where a large part of the population was unaware, or didn’t care, or ignorant. Like, what was it that drove him to do, to fight against his government? And you know, sort of learning about the Apartheid, and you go and try and make that cause real for yourself, and it doesn’t take too much researching to realize how abhorrent this system and the beliefs and propaganda. It was quite a despicable way of looking at people and humans and keeping them down. And so I think in some ways it seems simple, just trying to understand why he was doing what he was doing. That was the biggest thing for me, so you know, learning about the Apartheid and reading things like The Long Walk to Freedom, and Cry the Beloved Country, was just, you know, great Apartheid literature. There’s a bunch of really powerful and evocative sort of storytelling if you can go to it and just to try and base yourself in who this guy was, and that, for me, was: He’s a real guy, he’s still alive, he lived this, he believed this. That’s my way of honoring him and trying to show, try and understand him and put his cause up on screen. Because I think he’s on the right side of history with this. I think Tim is. I think they were absolutely in the right, and wholeheartedly agree with them, and I think most people do in this day and age. So, I guess that, and then there’s obviously accents, and the physical look, and you just have to try and craft it all around that.

ekm: You touched on about fifty different things I wanted to ask you, so I want to thank you for being so succinct. You know, it’s always very obvious when an actor is digging deep to find truth or simply taking a biopic for a paycheck, and you’ve played a number of either real people, or characters who are very, very real. I spoke with Daniel Radcliffe about this film — which by the way, I want to say, and I was going to say by way of segue, is absolutely fantastic. ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA: it’s wonderful. I loved it. I spoke with Francis Annan as well, and he had so many very important insights that are historically relevant, but also very topical for now. And something that Daniel Radcliff was telling me — and you know, obviously Tim Jenkin had a cameo in the film, and he had written the book, which was clearly the source — but Mr. Radcliffe was also able to speak to him. Did you have the same, sort of immediate connections to the real people, and how much of that was something you could directly draw from?

DW: Yeah, the first thing is there’s a documentary online, so I could hear him and see him, and I was really struck by his compassion and his humanity and his humility, and his values, and his strength. There’s a certain strength to Stephen. And then when we got further into the process, we were rehearsing in an old cinema and they projected a call in on Skype, and they projected Tim and Stephen at different times up on the screen, so we got to have these wonderful conversations about the Apartheid and why they did what they did and their life prior to it, with them about ten feet tall up on the cinema screen. It was a pretty surreal wonderful experience, and then subsequently I got to spend a little more time with him and get to meet him in person and chat.

ekm: That ten-foot-tall on-screen conversation must have been incredibly intimidating, and something to sort of say, Okay, well, now I need to grow a few more feet in order to match the spirit and the truth of the story.

DW: Totally. You know, it’s one thing to read about it and learn about it, and then having actual people tell you their stories from prison; you know, to literally be telling you…it’s something else. And both Dan and I, and Francis the director, left those meetings so inspired and filled with a desire to try and capture the story and tell it as best as possible. I’ve never had that quite in that way, but I was very much energized by just talking to them.

ekm: I’d asked Francis about whether this story — which obviously has got to be, for the subjects to be able to watch something so traumatic and powerful and dramatic that occurred in their real lives enacted onscreen — I mean, that has to be an incredibly surreal experience. But I imagine it has to be an incredibly surreal experience for you as well, being tasked with bringing that to life, and then sort of receiving feedback [from the real-life persons depicted]. Have you ever had any experience like that prior?

DW: It’s very tricky, I think, for people who have lived an experience, to see themselves portrayed and to know what was real and what wasn’t. What things rang true to them and what wasn’t ringing true, because at the end of the day, my task and Francis and Dan’s task is to tell a story. We’re telling a dramatic retelling of their truth and their history, so whenever you are doing that, they’re looking at every little detail and every little thing and questioning why that happened here. So one of the things I loved the most about the press tour we did and spending time with Stephen was having conversations about what decisions were made, why they were made, why they came to be, and discuss his uncertainties about things, and queries. So I really loved being able to do that, because it’s pretty rare that you get to sit down and have that sort of interaction with them, and vice-a-versa. I got to have conversations about my work and what-not. And they were quite happy with it. Stephen was very happy that the politics that got him essentially in Pretoria: they were a big part of the story as well. He was very gratified that we could’ve washed over that aspect of the story, but it was very important to [Francis]. In some ways it’s asking a pretty basic question in the film, of what is a better political action: if we’re going to fight our government, what is the best political action we could take? We could stay here and be martyred, and be a symbol for the AP, and the anti-apartheid movement, or we can humiliate the government and bust out of prison. And that would be a huge political act, and keep alive the spirit of the AC, which at that time I think Mandela had been in prison almost ten years. So, it’s a wonderful question wrestling at the heart of it all.

ekm: You touched briefly earlier on the fact that a lot of these themes are very topical, even in today’s climate, and something that really strikes me about the film is the fact that these themes are also applicable to just about everyone in any country in the world today, but the message is something that obviously is going to affect different viewers different ways. You know, do you toe the line, or do you rise up and resist? What do you personally hope that, whether it’s someone watching it in Canada, someone watching it in Norway — what are you hoping that people take away from this film?

DW: I see the core of this film to be about courage, and it’s about courage to stand up for humanity, for those around you, for your beliefs. And the consequence of potentially your own life, for these guys. Having the courage for them, literally unlocking a door and taking that step, the courage that is every step that they had to take. They could have been caught, and if they’d been caught they could have potentially been shot, and if not shot they would have had twenty five years added to their sentence; so the courage of being caught, trying to take this political action, I think that is the essence of this story, the heart of these guys and the humanity and the values that they had.

ekm: And I find that such a compelling true-to-life as it is, it’s also a compelling metaphor. How do we break through the unbreakable door? Well, we have to manufacture our own key. There’s something really beautiful and poetic about that.

DW: Absolutely. I couldn’t have said it better myself.

ekm: So, what’s next in the pipeline for you?

DW: I’m shooting something in April, but I’m really just looking for another story like this, that I connect with, that’s powerful. I mean, you talked about just taking jobs for a paycheck, and I really don’t want to be doing that. I want to be working on important material, and things like doing things with a positive social message, and are entertaining. So I’m on the hunt right now.

ekm: I think that you are one of those actors who is very much a chameleon; very much a Gary Oldman type, or — and this might be a crazy leap — a Christopher Guest, almost; where you don’t see the actor, you see the character. That is a tremendous skill, and I sincerely hope that ESCAPE FROM PRETORIA and anything you do subsequently gets you the attention that you deserve.

DW: Oh man, that’s a pretty bloody good compliment, I’ll take that. Gary Oldman. He’s one of the greats. I definitely look up to him for all his work. He’s amazing.

ekm: So one last question I’ll bug you with: your favorite Motley Crue song.

DW: (laughs) Oh, I think it has to be “Wild Side”

ekm: Very, very cool.

DW: Either that or “Danger.” I have two. “Danger” and “Wild Side.”

ekm: I’m kind of a “Shout at the Devil” guy myself.

DW: Oh yeah, not bad, not bad. It gets the energy going in the morning, that’s for sure.

Erik Kristopher Myers (aka ekm)

@ekmyers

https://www.facebook.com/ekmyers

____________________________

*Many thanks to sci-fi novelist Megan Morgan for transcribing these interviews as I recovered from a long illness. However, she loses a point for chronically using “Motely Cru” instead of “Motley Crue.”

**Written and directed by me, in black & white (except for the specific use of red).