When trying to explain the historical importance of comic books to a non-reader, I cite the types of stories typically contained, and the fact that, until recently, they weren’t filmable. We take contemporary blockbusters for granted, and forget the previous limitations of televised programming. There was no way to believably show something like AVENGERS: ENDGAME; it took STAR WARS to throw open the door to a new galaxy of potential, and even then we were decades away from the digital canvas. This, coupled with the modern trend toward serialized storytelling, has largely rendered the comic book obsolete beyond an appreciation for what the medium itself represents, rather than necessity.

If you think about it, comics weren’t just the place to go if you wanted to see characters doing impossible things in impossible environments; they were what television is today, particularly with the advent of The House of Ideas. Starting in the 1960s, comic books told ongoing sagas. You tuned in, followed an exciting narrative, and climaxed with a cliffhanger. If you wanted to see what happened next, you had to get the next issue. Even TV resisted a break from episodic storytelling until shows like BABYLON 5 came along to introduce a Primetime model that had already long existed in the form of Daytime Soaps. Yet it would still be years before superheroes would (or could) be accurately realized, dramatically, and even when they did, you’d have to wait three years between BATMAN and BATMAN RETURNS. Pick up a comic book, and you could follow the continuing adventures month after month, year after year.

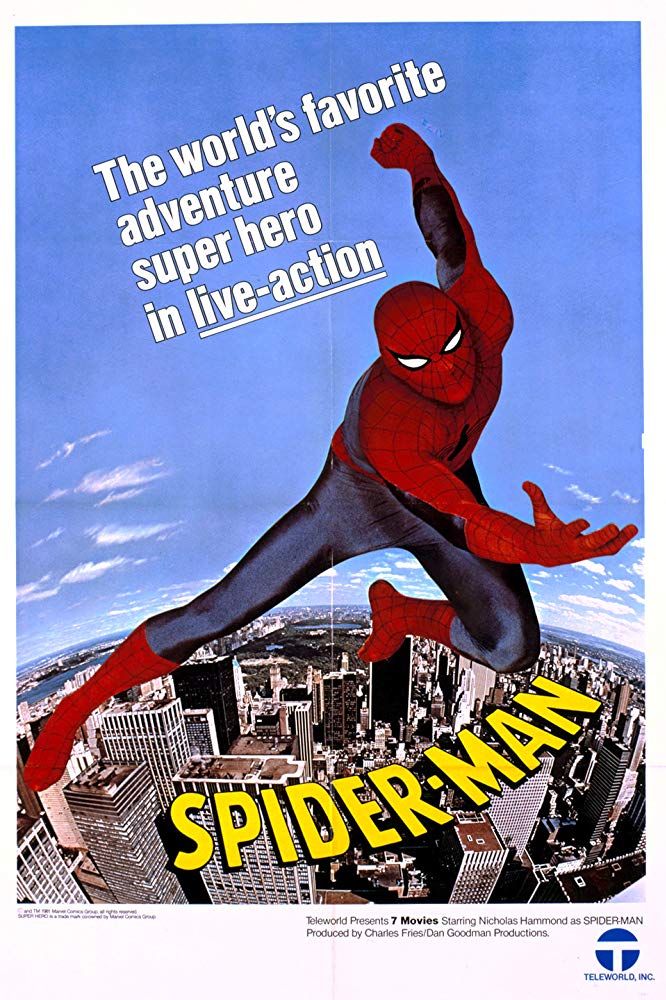

This isn’t to say there weren’t previous attempts to televise superheroes, and offer audiences weekly adventures. There were. Among them, THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN remains notable, and for two important reasons: 1) it was clearly embarrassed by its concept, and 2) it remains the most realistic depiction of the character possible. The two go very much hand in hand.

As a point of reference, there are many for whom Christopher Nolan’s depiction of Batman is their favorite, and I am not one of them. Nolan was openly passive-aggressive toward the source material, and jettisoned characters and iconography that didn’t make sense in the “real” world. The rest was redesigned. In some aspects this resulted in good storytelling; in others, it simply underlined only one of the many qualities that make Batman interesting. The fact that he remains one of the few costumed heroes who could, plausibly, do what he does, is a fascinating component, but to leave out the rest…well, leaves out the rest. It’s a creative limitation that shows, and has the unintentional side effect of backfiring on its very premise whenever Batman walks into a room. He’s completely out of place in his own movies. Nolan creates a universe striving so hard to be realistic, that it comes off like some dude dressed up in a bat costume just walked onto the crime scene at a Mob bank, and stood there barking at the cops like the victim of throat cancer, because that’s exactly what it’s like. Everyone would laugh, because it’s ridiculous.

THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN operates on the same level, but unlike the unfortunately-named DARK KNIGHT TRILOGY*, the “real world” approach results in the most fascinating live-action rendition of Spidey to date.

Have you seen the show? Probably not. It ran, sporadically, from 1977 to 1979, swinging high with a successful pilot movie** (ratings-wise), and running out of web fluid after thirteen episodes. Given the costs associated with production, and the proliferation of comic book characters in Primetime – namely, the Hulk and Wonder Woman – CBS produced far too little in the way of actual SPIDER-MAN content for the show to ever successfully catch on with viewers, but also made it virtually impossible to rerun in syndication. Aside from a very limited reissue on VHS, it’s fallen largely into obscurity, and exists today as a time capsule piece, readily available on Youtube…and, if you buy into my premise, remains the most fascinating WHAT IF? story never published by Marvel Comics.

So, first, let’s talk about that “embarrassed by the premise” thing I mentioned. Aside from Spidey, you had two very different comic book characters enjoying questionable lives on TV, and they couldn’t be more different. WONDER WOMAN was high camp. There was absolutely no pretense; the producers knew what they were producing, and the viewers knew what they were viewing.*** Then there was THE INCREDIBLE HULK, which played itself so straight that its opening title sequence managed to traumatize an entire generation of preschoolers. The show itself was more or less THE FUGITIVE, repackaged to include a rage monster in a silly fright wig; a decade later, the fledgling FOX network would in turn repackage THE INCREDIBLE HULK in one of its earliest original series, the short-lived (and unresolved) WEREWOLF. The plunderers are so often plundered.

Both series largely dropped the more fantastical elements from concepts that were about a Goddess and a screaming green man, respectively. This was the era of KOJAK and BARNABY JONES; villains wore tight beige pants and everything always looked vaguely sweaty. Super powers were limited primarily to the antagonist, and in the case of THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, this existing format would be adhered to more effectively than Nicholas Hammond being pulled up the side of a building while he (or his stunt man) pretended to climb by flailing his arms. In short: no Doctor Octopus. No Sandman. No Green Goblin. Even the “Night of the Clones” episode was unrelated to the exploits of one Miles Warren. With the exception of the titular hero, Aunt May, and J. Jonah Jameson, there were literally no ties to the comic book. Even Los Angeles stands in unconvincingly for New York, which is most apparent when you find yourself constantly worried that there are no buildings tall enough for Spidey to swing from. Instead, there were hypnotists, crooked industrialists, and religious cults, all with those tight beige pants, and all set to jazzy, tuneless music.

So: realism. CBS didn’t want any of that kiddie stuff, because that kiddie stuff alienates the older demographic. So what we got were thirteen episodes and a pilot movie about a college student, Peter Parker (played by Nicholas Hammond, formerly of the Von Trapp family, and who I’m convinced the 90s FOX KIDS series used as their visual model); and said college student is bitten by a radioactive spider. Gifted the abilities of a human arachnid, Peter goes on to use his newfound powers to battle the Leisure Suit Villain of the Week. THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, TONIGHT AT 8!

Now go with me down the rabbit hole for a moment. If you haven’t watched the pilot movie, please do so now; I’ve linked it at the bottom of this article. Watch it, enjoy it, and then swing on back, because I’m about to go to a very weird, but very logical place. Put on your Christopher Nolan goggles, and let’s talk about what I consider to be the accidental birth of The Most Realistic Comic Book Depiction Ever; so realistic, I Nouned it.

Let’s take the general concept at face value for a minute, and accept it, the same way we accepted some of the more fantastical elements in THE DARK KNIGHT. Buy into the concept that radiation exposure can allow a spider to pass its characteristics onto a human being via a playful nip, and that Peter Parker was somehow granted super powers rather than sudden hair loss, sterility, and, maybe, the incredible ability to lie still while maggots eat his face. Everyone with me? Good.

Now let’s remove every other sci-fi element from the Marvel Universe. Yes, I know I mentioned mind control, and a dalliance with a Spider-Clone, but THE DARK KNIGHT RISES danced uncomfortably on the edge of Comic Book Shit too, and no one complained about that. So just to be safe, let’s stick to the pilot movie, in which Nu-York is experiencing a crime wave involving Upstanding Citizens robbing banks and then committing suicide by slowly driving their cars into brick walls. Who’s retrieving the money from the crashed vehicles before the police arrive? Who is giving each Upstanding Citizen that curious lapel that, when activated, causes them to commit the crime? Who cares, since it isn’t the Scorpion, or Mysterio? In fact, the only riddle to solve is whether or not the Director mistook Michael Pataki for David White, and said, “Uh, I think you’re Captain Barbara, and you’re J. Jonah Jameson,” since both are playing the other one’s part.

In other words, programming a doctor and lawyer to commit a bank heist together might be some Crazy Shit in Real Life, but it’s pretty toothless for a Spider-Man story. The plots, in general, don’t much improve from the fanboy standpoint; and that’s exactly what makes it all so interesting. Peter Parker isn’t Bruce Wayne, though the film does introduce the discrepancy of showing Aunt May’s really sweet piece of real estate, which prompts the question of why Peter spends the entire movie hitting up every single person he meets to lend him forty-six dollars. An incongruous domicile notwithstanding, Peter Parker doesn’t have limitless resources at his disposal, and here he is, suddenly able to stick to walls, and he decides, for reasons the film never explains, that he is going to become a crimefighter. No, there’s no Uncle Ben here, and if there was, our brief introduction to Aunt May suggests that maybe Ben hired the burglar to put him out of his misery. With great henpecking there must also come great irritability.

As presented in AMAZING FANTASY #15, Parker stitches the costumes himself. It’s a leotard. Later writers would explain that he used discarded materials from the school’s dance class, but it still doesn’t address the obvious question of how this kid managed to create such a highly-detailed outfit. The eye-lenses alone have baffled kids for generations as they wrote to Stan Lee, asking how Peter could see through white fabric. Of the three cinematic iterations that would follow, the first two present a Spider-Man wearing getups that are anything but spandex; each one is worth more than my car. In making the uniform more photogenic, the plot hole becomes both deeper and wider, and in neither case is the suit’s creation explained. In the case of the third and most current version, Tom Holland is wearing a series of hi-tech and eye-pleasing costumes because of his affiliation with Tony Stark; however, when forced to go back to the original outfit he had designed for itself, it’s crude in the extreme, because he’s fifteen, and that’s what a fifteen year-old would make.

Such is the case in SPIDER-MAN ’77. While I wouldn’t go so far as to call the Spidey suit “crude,” as it has the fairly elaborate web design intact, and fits correctly, it’s still far from what Steve Ditko created on the page, and what John Romita refined. This has always been the bane of live-action comic book characters, up until Tim Burton decided to put Michael Keaton is a padded, rubber suit. It’s better-looking, but it’s unfaithful. Stan Lee would have us believe that these uniforms are made of fabric, and that they can tear, and they can be shredded. However, that pesky Real Life scenario also means that they’d look stupid, and that Spider-Man and Daredevil and all the rest would likely inspire laughter long before they inspired awe.

But in 1977, this is what Spider-Man would actually look like; in 2019, as I write this, it’s still what he’d look like, considering that while Holland’s homemade outfit in SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING might be the work of a teenager, it’s still designed to be less ridiculous than comics-accurate spandex. In other words, while an entire generation of kids (including myself) might have sat in stunned horror as the live-action Spidey appeared onscreen for the first time and looked nothing like the figure of power and dignity on the page, the fact remains that the page lies. That’s Spider-Man, kids: a dork in a dorky red and blue aerobics outfit. Also, Santa Claus fucks your Mom.

Then there’s the webswinging. I’m sure I wasn’t the only obnoxious child sincerely bothered by the fact that Spidey’s previously compact web shooters and utility belt were worn on the outside of his ballet dress like jangly disco jewelry; but the webs themselves were a whole separate issue, because the webs were clearly ropes. Just, unmistakably, ropes. They were white; there was no cross-hatching; they were ropes. The one image we see of a web line connecting to a flagpole pre-swing (and we see it often, as many of Spidey’s FX shots were repurposed throughout the series) is a herky-jerky shot of said web line wrapping itself around the pole on contact. It wasn’t hard to see that it was simply the rope being pulled away, played back in reverse. Couldn’t they have tried a little harder to make it look like an actual web at least…?

I don’t know — I think the more important question is whether Peter Parker could have synthesized webbing in the first place. Assuming he did actually come up with an elaborate formula for liquid-cable that could dissolve an hour after release, the Peter Parker we know and love would discover that the storm cloud that’s always following him around would suddenly begin raining money. But with great power, etc. Going with the premise that Nicholas Hammond was playing an actual college student who was actually bitten by a spider and actually had the enhanced ability to go out and fight crime, and if he actually created a web formula in the school lab, and actually created wrist gadgets that dispense the formula in the form of swing-ready web lines, the likelihood is that the stuff dispensed would look like ropes. Next time you gaze upon the hand-drawn image of a sleek, costumed Spider-Man webbing up a Bad Guy, translate it into the mental image of a dude in a Party City Spidey outfit, squirting out inconsistently-pressurized ropes that trail limply around a guy in beige pants and a fedora. MAKE MINE MARVEL.

Can he swing from a thread? Take a look overhead! What you’re seeing is a dangerous stunt that probably took hours to set up and execute. We’re not talking some swan dive from the Empire State Building, followed by an artful, last-minute skim across the city pavement before launching back into the sky; we’re talking about a stunt man wearing a harness, hopping off a mid-level building and holding on for dear life as he swings Tarzan-style to the next building over. One building, and one swing. Being able to stick to walls doesn’t necessarily mean that the Spider-Man presented here has the upper body strength necessary to propel himself along from Queens to Harlem and back again. Comic book Spidey certainly does; but again, what you’re seeing here is an actual stunt performed by an actual human being. It’s the first and last time, Baltimore fan films aside. This is what it would look like. Only Raimi’s first film would address the sheer terror of leaping from a rooftop, with only a thin strand of chord to support you from the Billboard of Bullshit below.

Even before we see the first sky swing, we’re treated to an insightful bit in which Peter is experimenting with his webshooters in the backyard. There’s a big, depressed-looking tree. He shoots a web/rope at one of the branches. Then, like an adult trying to play on a kid-sized playground, he awkwardly half-swings, half-falls, clutching a Spidey-sized cable that is — realistically — too thin to comfortably cling to. Hammond pretends he’s having a good time; the tree does not, and nearly falls over. All the while, that tuneless jazz music instructs us that this is supposed to be cool. It’s kind of sad, actually.

Remember how Peter Parker takes covert photos of himself battling villains and then sells them to The Daily Bugle? Yeah, I know, that technically makes him a con artist, but let’s not get into that right now; there will be time to discuss it later on. The point is: Peter can get shots no other photographer can, because he can web his camera up high, or in places right there in the thick of things. But even the comics had to address the impracticability of trying to get snaps while Kraven the Hunter is preparing you for burial; later writers would introduce camera sensors and other more plausible ways of obtaining shots of one sort while evading shots of another kind. But since we’re talking Real World, circa 1977, and we’re examining Spider-Man in the landscape of a CBS series, we have to assess the pics that Peter sells to Jameson — all of which look very much like staged publicity photos — and realize that, yeah, that’s probably what they’d look like, because Peter wouldn’t have time to fumble with the focus while battling three samurai warriors; he’d have to set up a tripod, a timer, and pose for the camera with a What, me…? sort of posture. If it’s lame, it’s because real life is lame, even when you’re Spider-Man.

The incredible special effects that would later bring Webhead to glorious life present an idealized Spider-Man: the embodiment of what countless artists have presented in countless stories. Is it realistic, though? Hard to say, because we can’t really be sure how a guy with Spider Powers would move, or jump, or punch. We certainly know his costume wouldn’t look like the ones worn by Maguire and Garfield and Holland, because he couldn’t have made those. The web shooters and web fluid couldn’t produce the stuff those guys have, either. Swinging from building to building would be terrifying, even at a height of thirty feet. Most importantly, the general populace would certainly be in awe of a guy wearing that outfit and doing those things, but not because he inspired us; we’d think he was a lunatic, and because we knew he was just one poorly-aimed web-rope away from a horrible and public death in the middle of Madison Avenue.

You want a “realistic” Spider-Man? Here he is. And this is exactly why fantasy is what these movies need in order to thrill us, and inspire us.

*While BATMAN BEGINS was merely “successful” at the Box Office, THE DARK KNIGHT was ginormous, for reasons extending beyond the merits of the film itself. Warner Brothers took no chances, and made sure all three words in said film’s title were included in the handle for the third flick (THE DARK KNIGHT RISES), despite the disharmony this causes when looking at the names of each installment in the trilogy. Hedging their bets, they doubled down and used it again, this time as the name of the series itself, just to make it clear that these Batman movies are related to that Batman movie: you know, the one with Heath Ledger in it. Was this an example of Suits not trusting Consumers, or Consumers being so inundated by Commercial Product that they required this reminder? Using unscientific research data-mined from experiences at Best Buy, as well as forty-three years living amongst the Humans, I conclude that this decision, overall, was made because people are fucking stupid.

**The director of the AMAZING SPIDER-MAN pilot movie was the impossibly-named Egbert Warnderink Swackhamer. Possibly the greatest missed opportunity Marvel ever experienced was in not pitting Spidey against a villainous thug called “The Swackhammer,” who nefariously Swack!s with hammers. Mr. Quesada, if you’re reading this, please reach out to me via social media so I can tell you where to mail the checks.

***The correct answer is “Both of them.”

Erik Kristopher Myers (aka ekm)

@ekmyers

https://www.facebook.com/ekmyers